The Science

NOTE: This article was updated in January 2026 to correct errors and expand on some of the concepts.

After we returned to Calgary from our December 29 Prairie Mountain sunrise hike, I started to wonder about the small anomaly that led us to pick that day. Specifically, the fact that the day with the latest sunrise does not align with the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere. Before I get into the science, here’s another photo from that memorable morning.

I did some research and learned the interesting astronomical reasons for this phenomenon. I first looked up the sunrise/sunset tables for southern Alberta. The solstice occurred at8:27 p.m. on December 21, but the latest sunrise occurred more than a week later. Not only that, the date of our earliest sunset was well before the solstice—way back on December 12, to be exact.

What’s going on here? After all, these differences are not small.

While it’s true that the solstice is the shortest day based on sunlight hours, it isn’t the shortest solar day, which is defined as the measured time for the sun to pass over a given meridian line from one day to the next. In fact, solar days are the longest in December. It’s important to note that solar days are not the same as clock days, which are the familiar 24-hour periods that we measure with our timepieces.

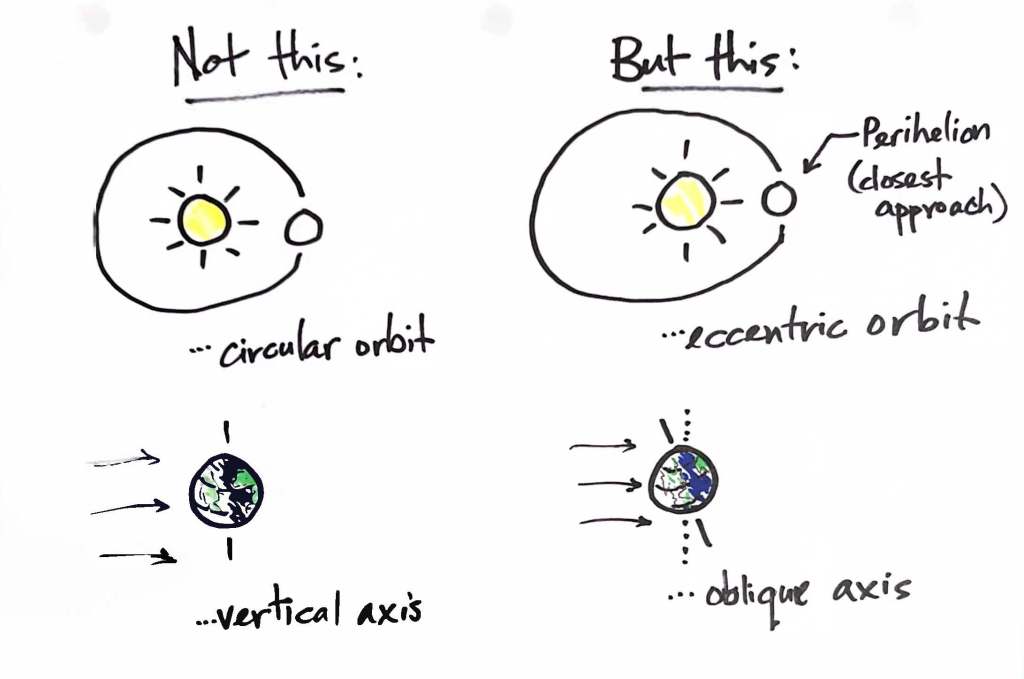

A recent article in Scientific American explains that there are two reasons for this counterintuitive result. With all credit to the excellent minutephysics video by Henry Reich (“Why December Has the Longest Days”) referenced in the article, I’ve reproduced the two reasons in the following chart.

First, the shape of the Earth’s orbit is not a circle but an oval, an ellipse. The difference between the earth’s nearest and farthest points from the sun is small, about 3 percent of its average orbital distance of 150 million kilometres. This matters because as the earth reaches its closest point (called the perihelion), it moves faster through space. This faster movement lengthens the solar day—again, that’s the time needed for a given line of longitude to come around the next day to align with the sun. This effect adds about eight seconds to the solar day.

Besides the eccentricity of the earth’s orbit, the tilt of its axis also contributes to the disparity between solar day and clock day. This effect, called the obliquity effect, lengthens the solar days by about 20 seconds around the solstices and shortens them by about 20 seconds around the equinoxes.

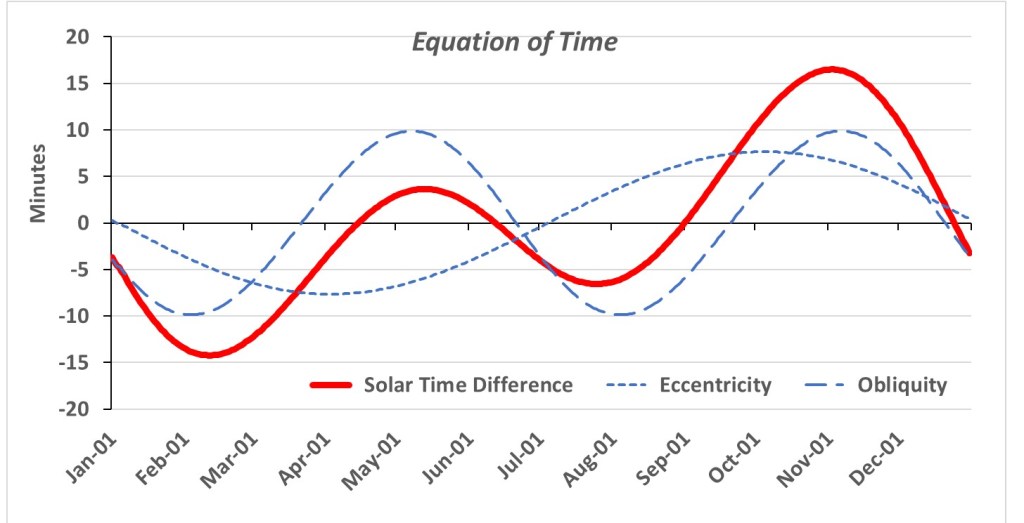

The impact of these two factors on the solar day is well known. There is even an equation of time to relate solar time to clock time. Mathematically, the effect is represented by two sine wave functions. The frequency of the eccentricity curve matches the earth’s annual rotation, and the tilt curve goes through two cycles each year. The figure below was generated on PlanetCalc. It shows how adding the curves results in solar days that are shortest in February and longest in December. There is also a smaller peak in the spring and a dip in the summer.

Because perihelion occurs close to the winter solstice (on January 2), the two day-lengthening effects are additive, totalling about 30 seconds a day at the peak in November. These “extra” seconds are pushed forward to subsequent days, making solar noon (the precise time that the sun reaches its highest point in the sky each day) later and later at that time of the year. And because sunrises and sunsets are symmetrical around solar noon, we get the observed result: the earliest sunset gets shifted backward (before the solstice), and the latest sunrise gets pushed forward (after the solstice).

As a final point, if you were to do an experiment in which you marked the tip of the shadow cast by a sundial each day at precisely noon, it would trace out a unique, elongated figure eight shape over the course of a year. That shape is called an analemma, and it is a graph of the equation of time. Changes along the vertical axis of the curve are due to the tilt of the earth (cycling between -23.5 degrees to +23.5 degrees), and changes along the horizontal axis are due to the eccentricity of the earth’s orbit.

The figure at left is the analemma plotted at noon GMT from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, England (Source: JPL Horizons Lab). I like this figure because it includes calendar notations, which make it easy to compare with the equation of time graph shown above.

Whew! I expected the answer to this question to be simple, but it’s taken me a few tries and a lot of soak time to understand. Somehow it seems appropriate, having just started a new year (and passed the perihelion), to recognize that the universe is full of mystery.

Until next time,

3 thoughts on “Prairie Mountain Sunrise, Part 2”