This is a short post, with the latest news. I’ve been busy compiling and editing photographs for my new BUMP Photo Run series. If you aren’t familiar with BUMP, it’s the Beltline Urban Mural Project, a vibrant project that has been brightening up our city since 2017. Check out my first piece here. You can read about the background of the project while enjoying photographs of some amazing art. Look for more posts very soon!

Canmore Public Library Event, Feb 12

UPDATED!

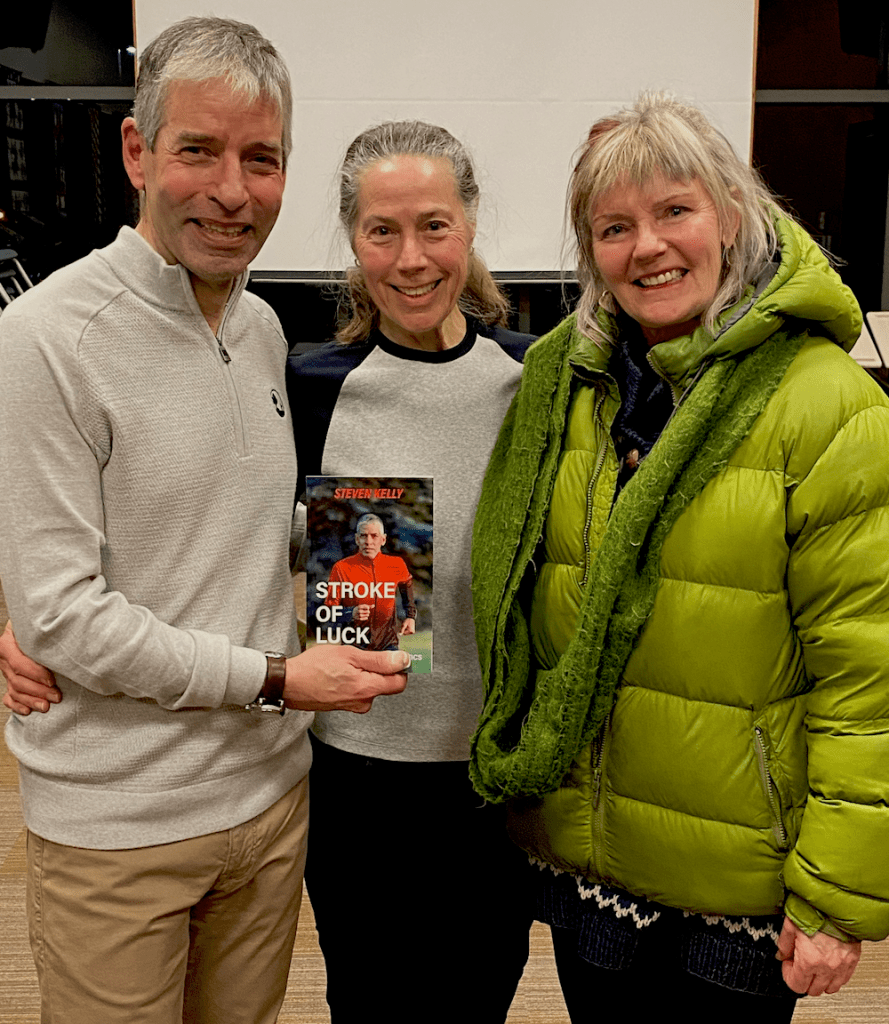

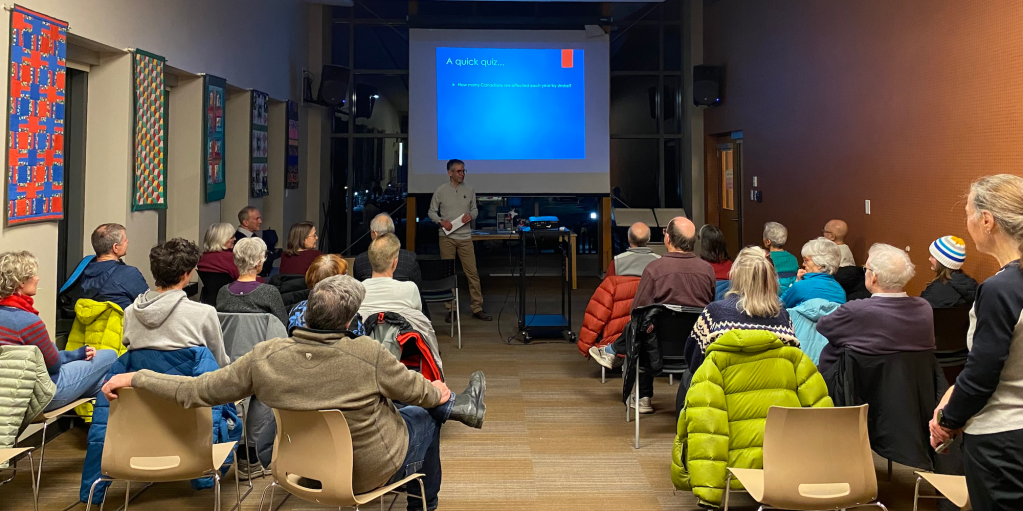

It was a wonderful evening in Canmore. The venue in Elevation Place was beautiful, we had a great turnout for our talk and an engaged audience. What more could we ask for?

Thanks to my friend, Don Crowe, for taking on MC duties, to Carey Lees of the Canmore Public Library for her flawless organization, and to all who attended. Thanks too, to Kylie and Tim at Strides Canmore, for their generous support of this event!

Here’s a synopsis of the talk:

- A brief personal introduction

- A collage of my running adventures (see below)

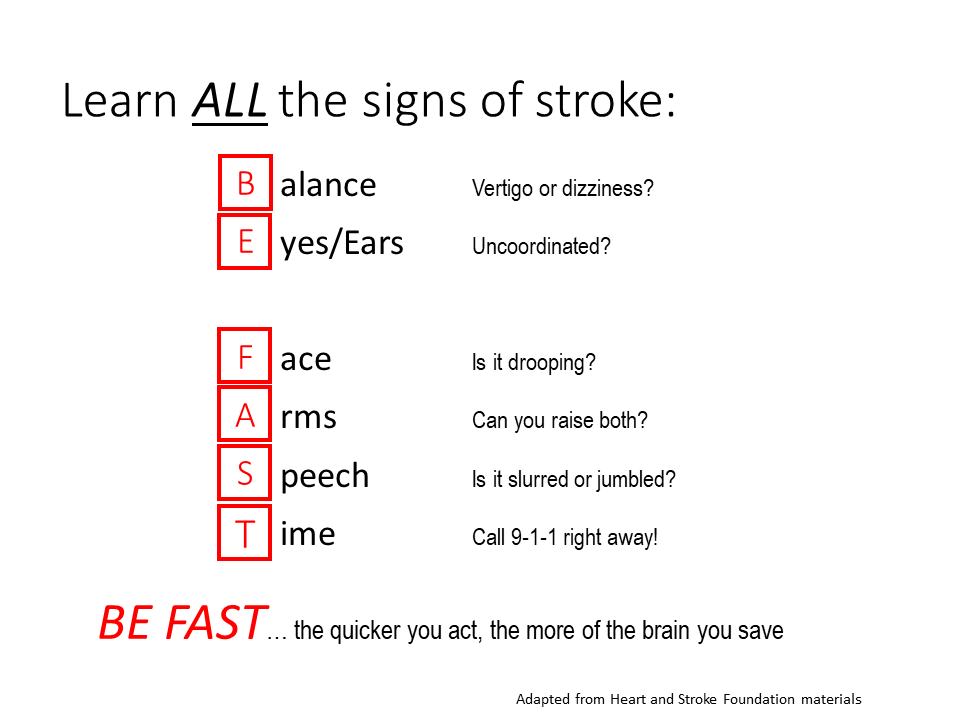

- Discussion of my stroke journey, including the useful phrase to remember stroke symptoms (readers of this blog will already be familiar with BE FAST)

Of course, I shared my three main messages, listed below:

- The importance of an active lifestyle

- Awareness of ALL the symptoms of stroke

- Raising funds to support the great work being done every day on stroke prevention and care at the Foothills Stroke Unit

You can read all the details in Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics. And there’s some news on that front: Cafe Books in Canmore will be carrying the book. So, if you live in Canmore, please drop into this unique bookstore and grab your copy!

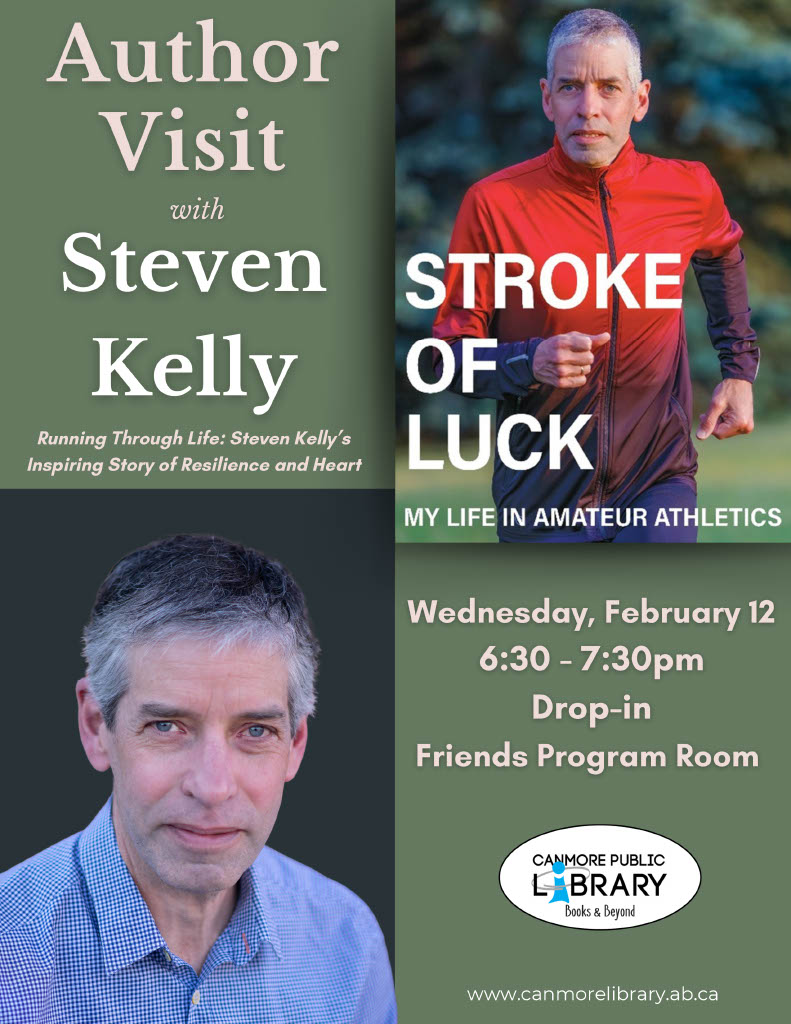

For anyone in the Canmore area this Wednesday (February 12), I’ll be speaking at an Author Event at the Canmore Public Library at 6:30 p.m. Join me if you can, for an informal (and informative) presentation of my story, as told in Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics. There will be a short presentation, a Q&A session, and some draw prizes. I’ll have copies of the book available for purchase, at a special event price. Proceeds from book sales support the great work being done every day in the Foothills Stroke Unit.

I’d like to thank the staff at the library for hosting us in your wonderful facility. Also, to my friends at Strides Canmore, thank you for spreading the word about this event, and for your ongoing support of my book project. I feel blessed to be part of the tremendous local running community… it’s second to none!

Finally, thanks to Dianne Deans, whom I had the pleasure of meeting at the CanStroke Congress in November. Dianne is an enthusiastic patient support volunteer for stroke victims at the Foothills Medical Centre. She kindly connected me with the Canmore library staff, which led to this event coming together. Thank you, Dianne!

Heart Month Sale Still On!

What better way to mark Heart Month than a healthy discount for online sales of Stroke of Luck?

Order your copy on Amazon, and save 20%. The sale will run through the end of February.

Until next time, be well and BE FAST!