Time is running out! Get your copy of Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics on Amazon in the next few days at a marathon-inspired 26.2% discount…

I recently wrote a piece about the common symptoms of stroke, and how public awareness campaigns, as effective as they are, can leave a gap in the number of strokes they help to detect.

I’ve been doing more reading on this subject, and turning up some interesting results.

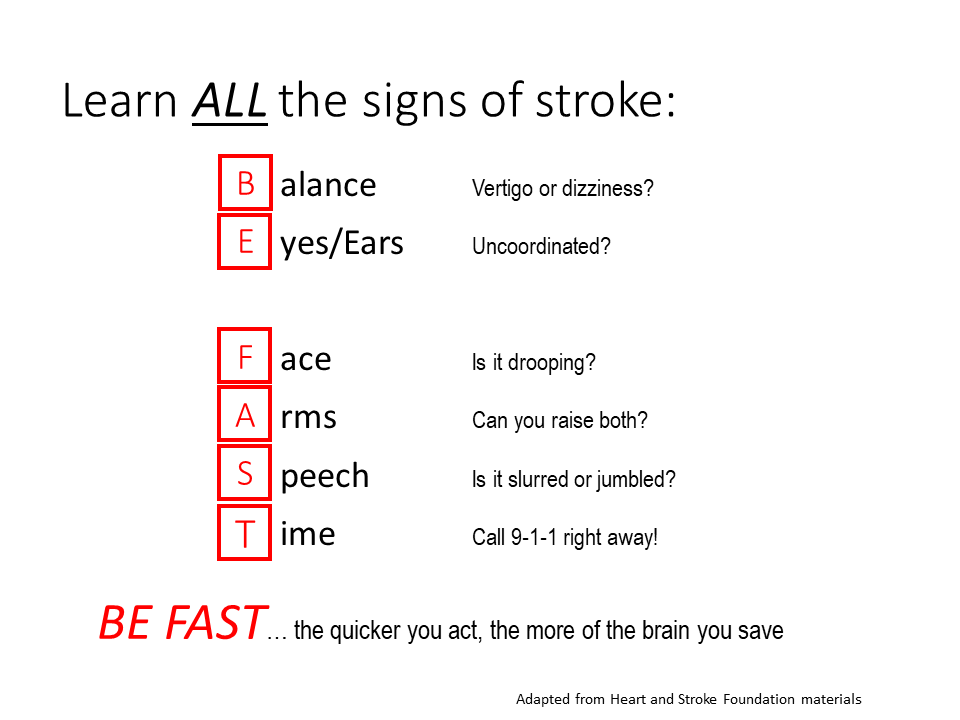

For years, the mnemonic F-A-S-T has been used to trigger us to recognize when someone may be having a stroke. Using this word, we should check the Face (is it drooping?), Arms (can you raise both?), and Speech (is it slurred?). “T” is for Time, as in don’t waste any before getting help.

Sounds good. But is it?

I mentioned in my previous piece that there’s more to the story. Why? Because F-A-S-T refers to ischemic strokes that occur in the carotid arteries. (There are two types of stroke: ischemic strokes, which occur when blood clots block flow in the arteries; and hemorrhagic strokes, which are associated with a rupture in a blood vessel.)

As a reminder, the carotids are the large arteries at the front of the neck. They account for about 80 percent of the total blood flow to the brain. In neurological terms, the carotids are the workhorses. And these are the arteries that, if they get blocked or damaged, can result in the symptoms noted above.

The balance of the blood flow to the brain is delivered in the vertebral/basilar artery system at the back of the neck. These arteries are smaller and they deliver blood to different parts of the brain. Not surprisingly, blockages in this network of arteries produce different symptoms. When vertebral blood flow is restricted, problems with balance and coordination of the eyes and the limbs can occur.

It has been recognized that a modified mnemonic would help detect strokes that occur in the vertebral arteries. BE FAST is already being recommended by some healthcare agencies as a more comprehensive trigger. Here, “B” is for Balance, and “E” is for Eyes (or ears). That makes sense to me, especially as I was having precisely those symptoms for weeks before I acted on it.

A study done by the University of Kentucky Stroke Center suggested that 14 percent of stroke patients were not identified using FAST. When BE FAST was applied, the proportion of identified strokes that were missed dropped to 4 percent.

In other words, more strokes could be caught if a wider screen were in use. Coincidentally, but maybe not, the number of strokes missed by FAST more or less matches the proportion of blood flow to the brain that originates in the smaller, but still important, vertebral arteries.

Another article I read recently on CNN Health addressed the different presentation of strokes between men and women. Interestingly, women may experience other stroke symptoms, beyond the parameters of even the broader, BE FAST, mnemonic.

Research summarized in the CNN article has shown that women may present with atypical stroke symptoms or symptoms that are more subtle and vague. In some cases, symptoms such as severe headache, generalized weakness, generalized fatigue, shortness of breath and chest pains, nausea and vomiting, brain fog, and even hiccups, may occur instead of or in addition to the symptoms noted above.

As to the reason why men and women experience stroke differently, scientists have come up with different theories. First, it’s about hormones. Age is another factor. There are other possible explanations too. I recommend reading the article to get the whole story.

It goes without saying that any symptoms that suggest a neurological problem should be acted upon immediately. No one ever needs to apologize for flagging a problem that may turn out to be nothing. It really is a case of being better safe than sorry.

As a final point, I’ve been spreading the word about stroke symptom cues when I speak to my running friends. There’s something appropriate about advising runners to BE FAST. After all, this should be an easy phrase for them to remember… it’s what they’re trying to do already!