There’s still time to get your copy of Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics for Christmas. Available on Amazon and through independent bookstores. Don’t delay!

There’s still time to get your copy of Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics for Christmas. Available on Amazon and through independent bookstores. Don’t delay!

Time is running out! Get your copy of Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics on Amazon in the next few days at a marathon-inspired 26.2% discount…

I recently wrote a piece about the common symptoms of stroke, and how public awareness campaigns, as effective as they are, can leave a gap in the number of strokes they help to detect.

I’ve been doing more reading on this subject, and turning up some interesting results.

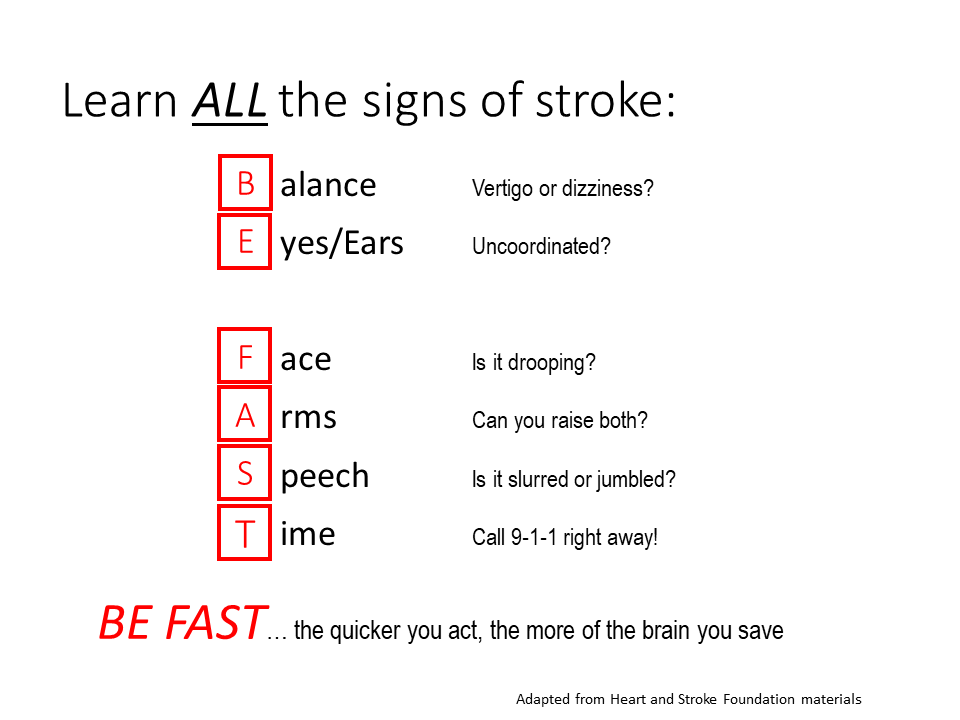

For years, the mnemonic F-A-S-T has been used to trigger us to recognize when someone may be having a stroke. Using this word, we should check the Face (is it drooping?), Arms (can you raise both?), and Speech (is it slurred?). “T” is for Time, as in don’t waste any before getting help.

Sounds good. But is it?

I mentioned in my previous piece that there’s more to the story. Why? Because F-A-S-T refers to ischemic strokes that occur in the carotid arteries. (There are two types of stroke: ischemic strokes, which occur when blood clots block flow in the arteries; and hemorrhagic strokes, which are associated with a rupture in a blood vessel.)

As a reminder, the carotids are the large arteries at the front of the neck. They account for about 80 percent of the total blood flow to the brain. In neurological terms, the carotids are the workhorses. And these are the arteries that, if they get blocked or damaged, can result in the symptoms noted above.

The balance of the blood flow to the brain is delivered in the vertebral/basilar artery system at the back of the neck. These arteries are smaller and they deliver blood to different parts of the brain. Not surprisingly, blockages in this network of arteries produce different symptoms. When vertebral blood flow is restricted, problems with balance and coordination of the eyes and the limbs can occur.

It has been recognized that a modified mnemonic would help detect strokes that occur in the vertebral arteries. BE FAST is already being recommended by some healthcare agencies as a more comprehensive trigger. Here, “B” is for Balance, and “E” is for Eyes (or ears). That makes sense to me, especially as I was having precisely those symptoms for weeks before I acted on it.

A study done by the University of Kentucky Stroke Center suggested that 14 percent of stroke patients were not identified using FAST. When BE FAST was applied, the proportion of identified strokes that were missed dropped to 4 percent.

In other words, more strokes could be caught if a wider screen were in use. Coincidentally, but maybe not, the number of strokes missed by FAST more or less matches the proportion of blood flow to the brain that originates in the smaller, but still important, vertebral arteries.

Another article I read recently on CNN Health addressed the different presentation of strokes between men and women. Interestingly, women may experience other stroke symptoms, beyond the parameters of even the broader, BE FAST, mnemonic.

Research summarized in the CNN article has shown that women may present with atypical stroke symptoms or symptoms that are more subtle and vague. In some cases, symptoms such as severe headache, generalized weakness, generalized fatigue, shortness of breath and chest pains, nausea and vomiting, brain fog, and even hiccups, may occur instead of or in addition to the symptoms noted above.

As to the reason why men and women experience stroke differently, scientists have come up with different theories. First, it’s about hormones. Age is another factor. There are other possible explanations too. I recommend reading the article to get the whole story.

It goes without saying that any symptoms that suggest a neurological problem should be acted upon immediately. No one ever needs to apologize for flagging a problem that may turn out to be nothing. It really is a case of being better safe than sorry.

As a final point, I’ve been spreading the word about stroke symptom cues when I speak to my running friends. There’s something appropriate about advising runners to BE FAST. After all, this should be an easy phrase for them to remember… it’s what they’re trying to do already!

Get your copy of Stroke of Luck: My Life in Amateur Athletics on Amazon, for a marathon-inspired 26.2 percent discount! The sale runs through the end of November.

By any reasonable measure, I shouldn’t be writing this. I shouldn’t be able to do much of anything. And yet, here I sit, thinking and typing. My typing is certainly no worse than it was five years ago. That was before my first running life abruptly ended.

Over the last month, I’ve had an opportunity to push against the limits of my compromised vertebral artery system. Vertebral arteries – “verts” – are the second major set of arteries that supply blood to the brain; the back of the brain to be precise. The verts account for about 20 percent of the total blood supply to the brain. When they are blocked, like mine were, the result is an ischemic stroke.

In 2017, I had a number of transient ischemic attacks, or TIAs, which are often called mini-strokes. The strokes were due to a blockage in my left vertebral artery. The result was a long stay in the Foothills stroke ward in Calgary.

I’ll repeat what I’ve said many times since then: the doctors that deal with stroke patients every day are heroes. I know this firsthand because the Foothills heroes stabilized me and saved my life.

The blockage in my left vertebral artery remains untreated. This is only possible because my body has made a rather ingenious adaptation to the blockage, by building secondary arterial connections to keep blood flowing to my brain. We were able to watch this in real time, on a video taken from an angiogram procedure. It makes for fascinating viewing.

As I pushed through a 16k run in the snow yesterday, or a 20k run in fine weather the Sunday before, I realized that I am a real-life experiment. While I am apparently able to cover these distances without too much trouble, it has not been a straight-line recovery. Just after my hospital stay, I had trouble walking around the block. Slowly but surely, I put my life back together. As you’ll gather from the title of this blog, I call it my second running life.

I barely managed a 500m walk/jog a month after my last TIA. A year later I finished a 5k race side-by-side with my wife. Last year we ran the First Half Half Marathon in Vancouver.

Now I’m at what I think is my upper limit. I can get through 20k, but not without discomfort. I know I’m at my threshold because my neck/shoulder are generally screaming for me to stop by the end.

Curiously, this is the same symptom I experienced before my strokes, when I was training at a much higher level. The pain was most severe during marathon buildups, and I’m certain that it was the first warning sign of the arterial problems I would have a few years later.

It occurred to me that I could perhaps use these pre- and post-stroke data points to estimate the change (if not the absolute amount) in blood flow to my brain. My assumption is that by comparing the usual measure of maximum oxygen uptake – the “VDOT” – I could arrive at an estimate of the amount of damage done to my vascular system by the strokes.

Before my hospitalization, I was training at a VDOT of between 50-52, based on my being able to run 1:25 to 1:30 for the half marathon. Last year, my wife and I completed a half marathon in 2:06, which suggests a VDOT of about 35. In both circumstances, I would consider myself to have been at my oxygen uptake limit.

Based on these empirical results, it would seem that I’ve experienced a reduction of between 30-35 percent in my ability to process oxygen in competitive running situations.

I’m not sure these estimates would have any value in a clinical setting, or whether it would be useful information in determining the next (if any) course of medical action. But it does make some sense, when you consider that I cannot come close to the kinds of performances I could manage five years ago. Even so, the fact that I can get through a strenuous run or race at all validates what I’ve come to see as the silver lining from this whole episode: I’ve been given a second chance, thanks to the remarkable machine that is my body. I know I mustn’t waste it.