Today’s run was just what I needed.

I had a late evening return flight from Ontario yesterday, so I was feeling a bit out of sorts as I parked next to the Glenmore Athletic Park (GAP) track. A high school track meet was in full swing. I watched from trackside for a few minutes, absorbing waves of energy and hearing the screams of hundreds of students as they cheered on their teammates. It motivated me to get going on my short and overdue run.

I’d been thinking for some time about a homage post to the GAP track. I should say the original GAP track (GAP 1.0), because a spiffy new facility is being constructed by CANA, just a short distance away. I have a lot of criticism for decisions coming out of Calgary city hall but this isn’t one of them. I can’t wait for the new facility to be finished.

The grandstands have been taken down and moved to the new track. The brilliant blue of the new surface looks magnificent and oh so ready for spiked shoes. Crews are working on the finishing touches, like landscaping. It will soon be the dawn of an exciting new era in track and field in Calgary.

It seems timely to say a few words about GAP 1.0. I’ll be honest. The place is definitely looking worse for wear. Chunks of Lane 1 are crumbling into the infield. Patches and cracks are plentiful, thanks to our winter freeze-thaw cycles. The spotting booth on the back straight has been taken over by pigeons.

I did a little research and found out that GAP 1.0 was built in 1962-63. It’s just a couple of years younger than me. No wonder it has cracks and wrinkles!

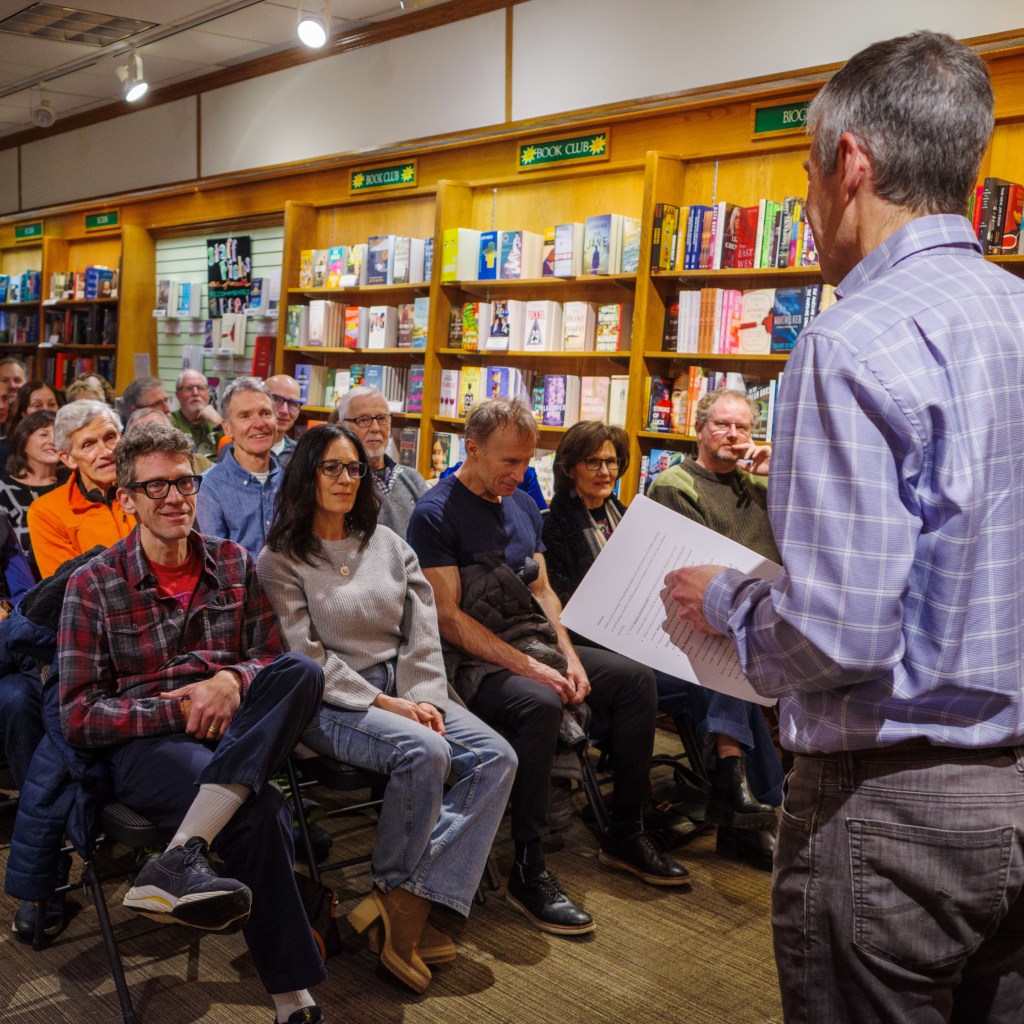

Despite these blemishes, the track has also been the site of countless track meets, interval workouts and road race finishes. I’ve personally done thousands of laps of the track, in all sorts of weather. And that’s a good segue to the fact that the Calgary running community has been second to none when it comes to keeping a lane or two of GAP 1.0 open through the winter months. All it takes is willpower and a lot of shovels, as demonstrated in this shot from October 2023.

Here’s a shot of an interval session from late March. It was one of those Calgary spring evenings when we started with water in the far corner and ended with sheet ice. No one complained when we decided to cut things short.

Or how about a photo from the 2019 Stampede Road Race? The park was a beehive of activity that morning, with lots of racing action and a pancake breakfast as our reward.

A recent track racing milestone got me thinking nostalgically about GAP 1.0. It was on May 6, 2024, the seventieth anniversary of Roger Bannister’s four-minute mile breakthrough on the Iffley Road track in Oxford, England.

It seemed fitting to make a brief pilgrimage, in pouring rain, to run four ceremonial laps in honour of this great achievement. After all, the GAP track is only 10 years younger than Bannister’s record. I pointed out the significance of the day to a young athlete who had just finished his track workout. He gave me a polite but puzzled smile. I secretly wished for him to do the same on the hundredth anniversary in 2054, running his commemorative laps on the new track.

In closing, I have many fond memories of running on the GAP 1.0 track. I don’t know what lies ahead, but if they do tear it down I’ll miss that familiar red surface, flaws and all. For years, it has been a great venue and meeting place for runners. It’s one of my favourite spots in the city.

So here’s to a good run for a fine old facility! And here’s to GAP 2.0… can’t wait to try out “big blue”.

Until next time, be well and BE FAST!